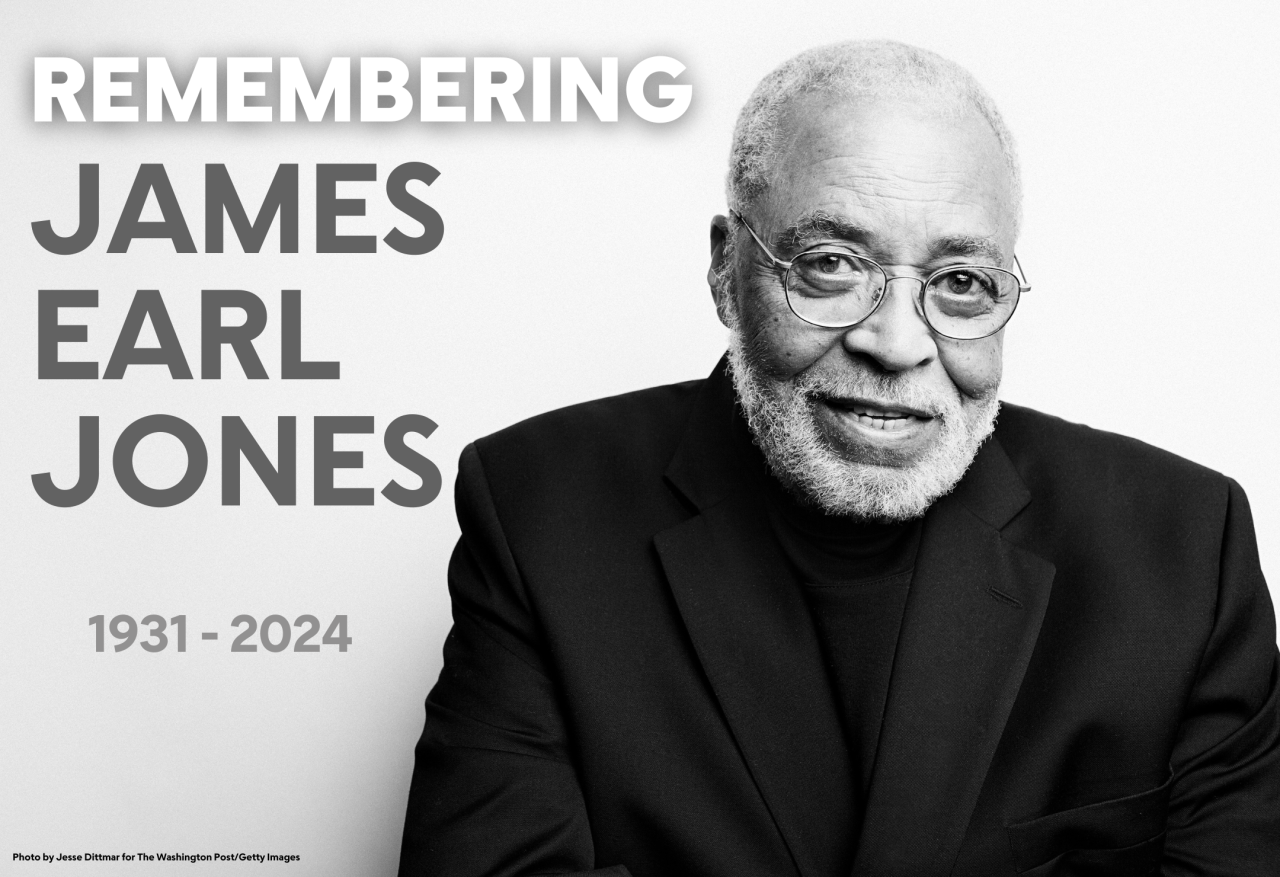

The world of theatre mourns the loss of the legendary James Earl Jones, who died at 93, leaving behind a legacy that will endure for generations. Known for his deep, resonant voice and commanding presence, Jones captivated audiences with powerful performances in iconic plays like You Can’t Take It with You, Driving Miss Daisy, and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. His work on stage showcased his remarkable range and talent, solidifying his place as one of the greatest actors in American theater. As we remember his life and career, we celebrate the incredible impact he made on the world of performance arts.

Plays James Earl Jones Brought to Life on Stage

You Can’t Take It with You by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman

Winner of the 1937 Pulitzer Prize for Drama

Photo by Joan Marcus, 2014 Broadway Revival

The family of Martin Vanderhof lives “just around the corner from Columbia University—but don’t go looking for it.” Grandpa, as Martin is more commonly known, is the paterfamilias of a large and extended family: His daughter, Penny, who fancies herself a romance novelist; her husband, Paul, an amateur fireworks expert; their daughter, Alice, an attractive and loving girl who is still embarrassed by her family’s eccentricities—which include a xylophone player/leftist leaflet printer, an untalented ballerina, a couple on relief, and a ballet master exiled from Soviet Russia. When Alice falls for her boss, Tony, a handsome scion of Wall Street, she fears that their two families—so unlike in manner, politics, and finances—will never come together. During a disastrous dinner party, Alice’s worst fears are confirmed. Her prospective in-laws are humiliated in a party game, fireworks explode in the basement, and the house is raided by the FBI. Frustrated and upset, Alice intends to run away to the country, until Grandpa and Co.—playing the role of Cupid—manage not only to bring the happy couple together, but to set Tony’s father straight about the true priorities in life. After all, why be obsessed by money? You can’t take it with you….

Driving Miss Daisy by

Winner of the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for Drama

Photo by Jeff Busby, 2013 Australian Production

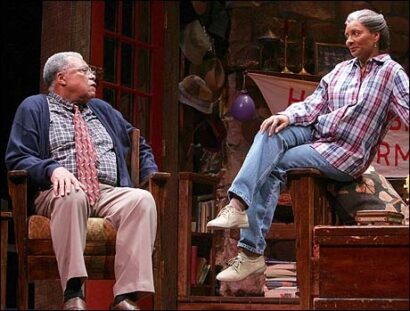

The place is the Deep South, the time 1948, just prior to the civil rights movement. Having recently demolished another car, Daisy Werthan, a rich, sharp-tongued Jewish widow of seventy-two, is informed by her son, Boolie, that henceforth she must rely on the services of a chauffeur. The person he hires for the job is a thoughtful, unemployed black man, Hoke, whom Miss Daisy immediately regards with disdain and who, in turn, is not impressed with his employer’s patronizing tone and, he believes, her latent prejudice. But, in a series of absorbing scenes spanning twenty-five years, the two, despite their mutual differences, grow ever closer to, and more dependent on, each other, until, eventually, they become almost a couple. Slowly and steadily the dignified, good-natured Hoke breaks down the stern defenses of the ornery old lady, as she teaches him to read and write and, in a gesture of good will and shared concern, invites him to join her at a banquet in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr. As the play ends Hoke has a final visit with Miss Daisy, now ninety-seven and confined to a nursing home, and while it is evident that a vestige of her fierce independence and sense of position still remain, it is also movingly clear that they have both come to realize they have more in common than they ever believed possible—and that times and circumstances would ever allow them to publicly admit.

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1974 Broadway Version) by

Photo by Sara Krulwich, 2008 Broadway Revival

Brooks Atkinson’s review in the The New York Times called it “a stunning drama…It is the quintessence of life. It is the basic truth.” Atkinson went on to write, “In a plantation house, the members of the family are celebrating the sixty-fifth birthday of the Big Daddy, as they sentimentally dub him. The tone is gay. But the mood is somber. For a number of old evils poison the gaiety—sins of the past, greedy hopes for the future, a desperate eagerness not to believe in the truths that surround them…Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is a delicately wrought exercise in human communication. His characters try to escape from the loneliness of their private lives into some form of understanding. The truth invariably terrifies them. That is one thing they cannot face or speak…As the expression of a brooding point of view about life, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is limpid and effortless. As theatre, it is superb.”

The 1958 version of this play is also available for nonprofessional productions.

The Best Man by

Photo by Sara Krulwich, 2012 Broadway production

The New York Post describes the plot as follows: “…William Russell, the ex-Secretary of State, is a wit and scholar with high liberal principles, beloved of the eggheads and suspected by practical politicians. Joseph Cantwell is a ruthless and hard-driving young man, a dirty fighter who will let no scruples stand in the way of his ambitions. And Arthur Hockstader is an ex-President, who loves politics for their own sake, admires a rough-and-tumble battler more than a chivalrous one, and is determined to have the final say in the selection of his party’s candidate…The ruthless young man has got hold of papers indicating that his rival once suffered from a mental crackup, which he is all set to use. Then his scrupulous antagonist comes across some incriminating evidence about Cantwell, which he is loath to produce. The scruples don’t appeal to the ex-President, who enjoys seeing the boys fight. All of this provides the framework for some vivid and interesting scenes in which Mr. Vidal contrasts the minds, emotions and fighting spirits of the two candidates…”

On Golden Pond by

Photo by Joan Marcus, 2005 Broadway Revival

This is the love story of Ethel and Norman Thayer, who are returning to their summer home on Golden Pond for the forty-eighth year. He is a retired professor, nearing eighty, with heart palpitations and a failing memory—but still as tart-tongued, observant, and eager for life as ever. Ethel, ten years younger, and the perfect foil for Norman, delights in all the small things that have enriched and continue to enrich their long life together. They are visited by their divorced, middle-aged daughter and her dentist fiancé, who then go off to Europe, leaving his teenage son behind for the summer. The boy quickly becomes the “grandchild” the elderly couple have longed for, and as Norman revels in taking his ward fishing and thrusting good books at him, he also learns some lessons about modern teenage awareness—and slang—in return. In the end, as the summer wanes, so does their brief idyll, and in the final, deeply moving moments of the play, Norman and Ethel are brought even closer together by the incidence of a mild heart attack. Time, they know, is now against them, but the years have been good and, perhaps, another summer on Golden Pond still awaits.

Of Mice and Men by

Two drifters, George and his friend Lennie, with delusions of living off the “fat of the land,” have just arrived at a ranch to work for enough money to buy their own place. Lennie is a man-child, a little boy in the body of a dangerously powerful man. It’s Lennie’s obsessions with things soft and cuddly that have made George cautious about who the gentle giant, with his brute strength, associates with. His promise to allow Lennie to “tend to the rabbits” on their future land keeps Lennie calm, amidst distractions, as the overgrown child needs constant reassurance. But when a ranch boss’ promiscuous wife is found dead in the barn with a broken neck, it’s obvious that Lennie, albeit accidentally, killed her. George, now worried about his own safety, knows exactly where Lennie has gone to hide, and he meets him there. Realizing they can’t run away anymore, George is faced with a moral question: How should he deal with Lennie before the ranchers find him and take matters into their own hands?

Paul Robeson by

A powerful chronicle of the life of Paul Robeson, taking us from his childhood in New Jersey to his adult life around the world. An All-American athlete and a lawyer with Columbia Law School credentials, Robeson faces the racism prevalent in society in early part of the twentieth century. He strives to rise above, and it is his triumph in that struggle that turns Robeson into a modern day hero. Realizing the racist system would not allow him to practice as a lawyer, Robeson turns to singing, something he had learned well in the church choir. His singing leads to acting and his acting, with all the accolades due a master, leads him around the world. But every place he visits he sees the strains of racism in its many forms. The more he sees, the more he speaks out, using the his influence and stature to try and enlighten those around him. After some time in Europe, he returns to the United States to perform and speak out about the injustices in the country he loves. Confronting racism again, he sticks to his values, adhering to no party line, but is accused of being a Communist, an agitator and much more. He is blacklisted and his passport is revoked, but he goes on speaking out whenever he can. For eight years he fights to clear his name. Finally, the social climate begins to change and towards the end of his life, Robeson’s passport is reinstated along with some of the glory and respect he earned along the way. There is still far to go, but Paul Robeson remains a beacon to those struggling to make this world a better place. This play is a powerful look at the many facets of Robeson the man, as well as Robeson the star. It is a tour-de-force for any actor.

Sunrise at Campobello by

Brooks Atkinson in The New York Times, describes “The play covers thirty-four months when F.D.R.’s crisis was a private one—from the day in August, 1921, when he was stricken by infantile paralysis at his summer home at Campobello, in Canada, to the day at Madison Square Garden in June, 1924, when he was able to stand on his feet long enough to nominate Al Smith for President of the United States …”